The Functional Alternative

The Functional Alternative

For some time now, I’ve been interested in functional programming. I had heard that it was an alternative to imperative programming (OOP languages, including PHP, are considered imperative languages) and if you sniff around you can find snarky comments by functional programmers about OOP. For the most part, though, the concern and need for functional programming has centered around multi-threaded and multi-core programming. If you can imagine two different threads using two different cores in your computer working in parallel to process a single giant list or array, you can understand how useful it is to divide the array in half and have different threads process each half. Since about 2005, all computers (except Raspberry-Pi types) are multi-core. Even my old iPhone 4S has a dual core A5 processor. With multi-threaded and parallel programming, though, you have to rejoin the multiple threads once each is finished to get a final result. Here’s where you have to be careful because you want to be sure that the values you’re handling have not changed in one thread and not the other or differently in both threads. You want to use immutable values to avoid surprises when the threads’ results are re-joined.

Where to Start?

A good starting point is Functional Programming in PHP by Simon Holywell. It’s about as simple as a book on functional programming can be, and you’ll find lots of examples. If you’re looking for material on lambda (λ) calculus and functional programming in PHP, you’ll only get a chapter that is ¾ of a single page, but Holywell goes on to say in the ever-so-brief chapter (chapter-ette?) on PHP lambdas,

…but just about every piece of functional code ever written makes use of lambda functions, and they are an important building block to add to your tool kit and should be mastered ….

Not to overstate a point, but Holywell is absolutely right, and so the reader is left wondering, why so brief a discussion of lambdas–a chapter that’s only three-quarters of a page? Well, the rest of the book has lots of lambda functions in use, and I imagine that the author figured the reader would be able to work it out on his/her own. (Maybe this point might be re-thought in the next edition of the book and the chapter be expanded.) In the meantime a useful online source can be found at Lambdas in PHP on the phpbuilder site.

If you really want to go nuts on functional programming, you can learn Haskell. On October 14, 2014 (in a couple weeks!) edX (the Harvard/MIT initiated free online course program) is offering Introduction to Functional Programming through The Netherland’s premiere technical university, Delft University of Technology. In the past I’ve learned that whenever I learn another programming language, I can always bring something back to PHP. Besides, the course introduction notes that PHP is one of the languages that has incorporated functional programming structures into its lexicon. You can take the course for free or get a certification for about $50. It’s 6 weeks long and will take between 6-8 hours a week of study.

For a quick and dirty differentiation between imperative programming and declarative (functional) programming, Microsoft has a nice little anonymous table that summarizes the difference. Being Microsoft, they put in a plug for their products and point out that C# can handle both functional and imperative programming. Since PHP 5.3, PHP too handles both types of programming; so we’re not dealing with an either or situation when it comes to OOP and functional programming in languages like PHP and C#.

So What Are Lambdas?

Lambda functions are anonymous functions, introduced in PHP 5.3.0. Essentially, a lambda function is one that stores an immutable value in a variable. For example,the following class has incorporated a lambda function to calculate the square of a value as part of the method doLambda().

< ?php class Lambda1 { function doLambda() { $lambda_func = function($stuff) { return $stuff * $stuff; }; echo "The square value is: " . $lambda_func(8) . ""; } } $worker=new Lambda1(); $worker->doLambda(); //Results - The square value is: 64 ?> |

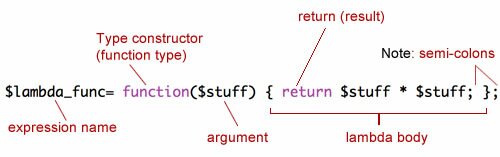

To call a lambda function an anonymous function is true, but to assume that all anonymous functions are lambda expressions criminally oversimplifies the lambda calculus behind lambda expressions. To help move on in understanding of PHP lambda expressions stated as anonymous functions, take a look at Figure 1.

Figure 1: Elements of a lambda expression

The parts of a lambda function are pretty straightforward, and you have to remember to add the semi-colon (;) after the lambda body in addition to the one at the end of expressions within the lambda body. Otherwise, it looks pretty much like a named function without the name.

Essential is the requirement to include the return statement in the lambda expression. In fact, it’s probably a better programming practice to use a return statement with all methods; a practice I’ve often overlooked myself. (See No Side Effects below.)

Continue reading ‘PHP Functional Programming Part I: An Introduction’

An Easy Start

An Easy Start

Recent Comments