Because PHP is a server-side language, you will have times that you need to rely on client-side languages like CSS, JavaScript and even HTML5 to accomplish certain tasks. In developing the CMS, I realized that while incorporating JavaScript, CSS and HTML5 in heredoc strings, I’d established a barrier between PHP and everything else by only allowing these other languages to interact with PHP through objects. Of course, this is because PHP has emerged into an OOP language and the others have not.

Because PHP is a server-side language, you will have times that you need to rely on client-side languages like CSS, JavaScript and even HTML5 to accomplish certain tasks. In developing the CMS, I realized that while incorporating JavaScript, CSS and HTML5 in heredoc strings, I’d established a barrier between PHP and everything else by only allowing these other languages to interact with PHP through objects. Of course, this is because PHP has emerged into an OOP language and the others have not.

What I failed to take into account is the fact that it’s perfectly possible for OOP structures to interact with non-OOP structures. To some extend that has been done with HTML/CSS UIs and PHP design patterns in several examples. That seems to work out fine, but where you want to use dynamic variables for more responsive HTML pages, we’re back to encapsulating HTML (along with Javascript and CSS) into heredoc strings in PHP. There’s nothing wrong with that, and there’s much to be said for having a fully integrated OOP design pattern with a pure PHP engine.

A Simple Functional JavaScript Sniffer

The problem I discovered in a pure PHP design is that other design possibilities are overlooked. The primary style tool for HTML documents is CSS, and the media queries in CSS3 are designed to be responsive to different devices—namely, those brought about by mobile computing. Sometimes (and I do mean sometimes) that solution seems to work fine. Other, times, however, the media queries fail to capture that chunk of CSS3 code that formats for the desired device. On top of that, it can be difficult calling up certain jQuery mobile files—or any other files—from CSS alone. In many ways, libraries in jQuery have proven to be far more robust than CSS3 alone and far easier to deal with. In several respects, probably in most, neither CSS nor jQuery mobile are programming so much as they are styling tools. As such, they’re the tail of the programming dog. This is not to say they’re less important; they’re just not programming.

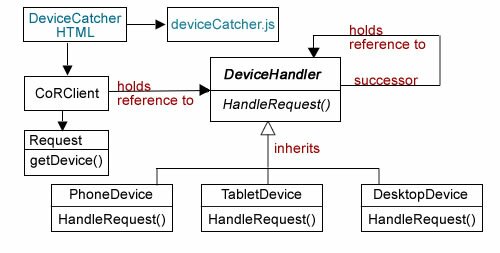

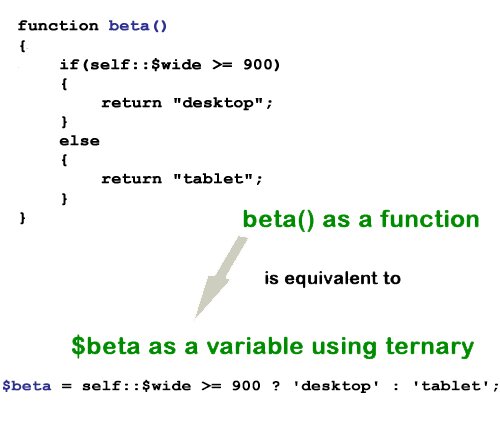

So, to sort out the devices looking at our pages, (moving away from CSS media queries) is a programming task. In several other entries on this blog, I’ve looked at ways to sniff through the possible devices, and I think we need to conclude once and for all that user-agents are next to useless. So, by exclusion, we’re left with screen width. So,begin by looking at this simple JavaScript sniffer using two lambda functions:

//Save as file name "jsniff.js" var wide = screen.width; var beta=function() {wide >=900 ? window.location.href="Desktop.html" : window.location.href="Tablet.html";}; var lambda=function() {wide <= 480 ? window.location.href="Phone.html" : beta();}; |

In past posts I’ve used the Chain Of Responsibility (CoR) design pattern to do the same thing using either user agents (forget about it!) or width determined by a JavaScript object. The little JavaScript lambda functions do the same thing, and while at some point of granularity your may wish you had your CoR pattern, generally, I think that there’s enough with the three general categories at this point in time to deal with multiple device. Use the buttons to test the functions. (Try it with your phone and tablet too.) Click PlayA for the sniffer and PlayB for the PHP functional alternative to the switch statement. The download button downloads the source code for both.

![]()

![]()

![]()

The process is pretty simple both from a programming and a lambda calculus perspective. From lambda calculus we get following definitions of true and false:

true := λx.λy.x

false := λx.λy.y

As algorithms, we might consider the following:

function(x, y) {return x;};

function(x, y) {return y;};

So, that means:

function (10,20) = 10; ← true : Is 10

function (10,20) = 20; ← false : Not 10

That’s not exactly lambda calculus, but it’s along those lines that we can eke out an idea. (If you’re thinking, “What about function(10,10) that would appear to be both true and false,” you see what I mean.)

So now we’ll add the values a and b and reduce it:

((λx.λy.x) a b) -> ((λy.a) b) -> a

That replaces λx with (λy.a) b and then a. So a is a. Well, it sounds true!

Then for false we have:

((λx.λy.y) a b) -> ((λy.y) b) -> b

In looking at this, we see that if a is a its true; otherwise it’s b which is not true. That’s pretty much like if-then-else. If true a, otherwise it’s b.

So the line in JavaScript would be a ternary:

lambda = function(a) { return a ? a : b ;};

as well as in PHP,

$lambda = function($a) { return $a ? a : $b ;};

For now, that’s enough linking up lambda calculus with Internet languages. With our JS “sniffer” using a simple HTML call, we can get the page configuration we want for our device based on the window size:

|

Try it out. It’s easy to write and it’s practical. What’s more, you can see how close everything is to a Boolean type decision. (The different device HTML5 files are in the materials in the download package; one of which uses the jQuery Mobile formatting.)

I Don’t Need No Stinkin’ Switch Statement

One of the nice things about functional programming is that it made me re-think how I was programming. One of the areas where I thought I’d be able to boil down an algorithm to something more compact came when I decided to break down a calendar output into four weekly segment. Using a jQuery calendar, I could pick a day and pass the information to a PHP class for processing. Initially, the switch statement came to mind as a solution in something like the following:

$d=$this->numDay; switch ($d) { case ($d >=1 && $d<=7): return "jquery"; break; case ($d> 7 && $d<= 14): return "haskell"; break; case ($d> 14 && $d<= 21): return "php"; break; default: return "racket"; } |

In looking for a range, each case acts like a little function. So why not use lambda functions in PHP to do the same thing. Each query (case/function) either returns a value or goes on to the next case. Here’s what it looks like:

$gamma=function($d) {return $d > 14 && $d <= 21 ? "php" : "racket";}; $beta = function($d) use ($gamma) {return $d > 7 && $d <= 14 ? "haskell" : $gamma($d);}; $lambda = function($d) use ($beta) {return $d >=1 && $d <=7 ? "jquery": $beta($d);}; return $lambda($this->numDay); |

The last used lambda function is the first in the list ($gamma). That’s because in order for the subsequent function to call them with the use statement, the function used must be defined before the one using it. In functional programming, the use of one function by another is referred to as a closure.

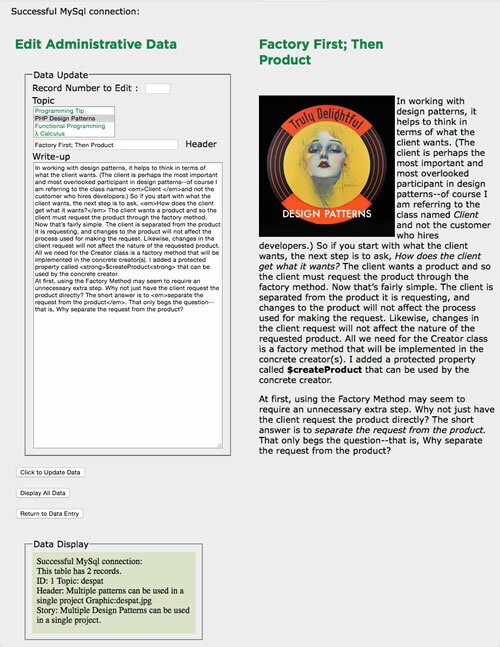

The Language Mix-Master

With the key parts in place, take a look at the different parts and languages used. First of all, the program begins with an HTML5 UI. It links to the jQuery UI JavaScript files and the CSS files. A further stylesheet links to the local CSS.

|

A form links to a PHP file where it passes the selected datepicker() value. The iframe tag provides a visual feedback embedded in the HTML page. (Note: Remember, with HTML5, iframes are no longer evil.)

Finally, using a single PHP class, the selected date is reconfigured to an integer and evaluated by the lambda functions described above in lieu of a switch statement:

error_reporting(E_ALL | E_STRICT);

ini_set("display_errors", 1);

class LangWeek

{

private $dateNow,$dayMonth, $numDay;

public function __construct()

{

$this->dateNow = $_POST['pick'];

$this->dayMonth=substr($this->dateNow, 3,2); // Start 03 : 2Length

$this->numDay = intval($this->dayMonth);

echo "

|

Fortunately the jQuery date picker passes the date as a consistent string mm/dd/yyyy, and so the only requirement is to use a substring to find the day of the month and convert it to an integer. This is passed to the chooseLanguage() method that employs the lambda functions.

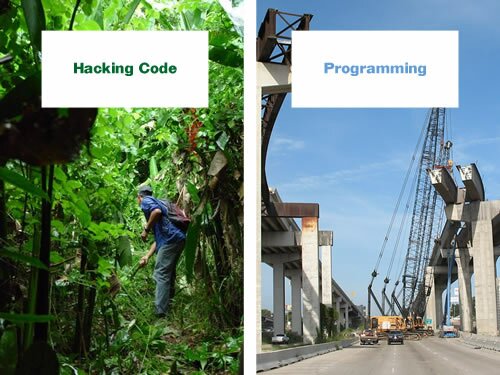

Mixing it Up

While this blog is dedicated to PHP Design Patterns and their application, I believe that PHP programmers should explore beyond OOP and try out different kinds of programming within an OOP framework, which happily exists within a Design Pattern. The willingness to explore and experiment keeps programming fresh and interesting in any language.

A CMS is only as good as the administrative module, and the one provided here is fully functional based on a simple work flow. You can change the UI and work flow to best fit your own, but you have the flexibility design patterns offer; so making changes to fit your needs (or those of your customers) should not be difficult.

A CMS is only as good as the administrative module, and the one provided here is fully functional based on a simple work flow. You can change the UI and work flow to best fit your own, but you have the flexibility design patterns offer; so making changes to fit your needs (or those of your customers) should not be difficult.

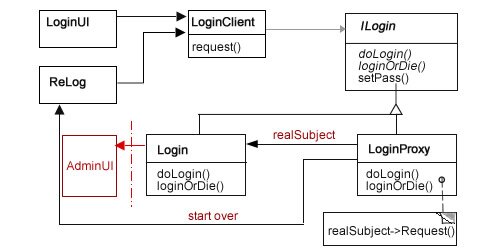

On this blog, the Protective Proxy pattern has several different implementations, and if you’d like to refresh your memory, this

On this blog, the Protective Proxy pattern has several different implementations, and if you’d like to refresh your memory, this

I’m not a graphic designer, and so I depend on others for the graphic elements and arrangement of my Web pages. However, I strive to make a site that is clear, easy to understand and useful. My focus is on good user experience (UX) and information design—clear communication with the user. In order to have good UX, you need to know something about , and if you don’t, check out the RWD link. Further, if you are unfamiliar with the approaches to RWD, I’m sold on the

I’m not a graphic designer, and so I depend on others for the graphic elements and arrangement of my Web pages. However, I strive to make a site that is clear, easy to understand and useful. My focus is on good user experience (UX) and information design—clear communication with the user. In order to have good UX, you need to know something about , and if you don’t, check out the RWD link. Further, if you are unfamiliar with the approaches to RWD, I’m sold on the

In previous posts on this blog, I’ve

In previous posts on this blog, I’ve

Recent Comments