The Problem with Globals

The Problem with Globals

Earlier this summer I completed a course through Rice University on Python. It was an introduction to making games with Python, and the four professors who taught it, did so brilliantly. One of the nagging issues that came up early was the use of global variables. In a clear explanation of the difference between local and global variables, virtually identical to PHP, we went through several game development exercises. At the very end of the class, however, we were admonished not to use global variables.

Online, you will find plenty of reasons to avoid globals in every computer language, but the main reason is one of maintainability. Because globals are accessible to all functions, their state can be changed by all functions. As a result, you may get unexpected outcomes that can be very difficult to track down, especially in larger programs. It’s like having a wild hare running through your program.

Encapsulation and Global Variables

Let’s start off with a simple example of global troubles. The following two programs represent sequential/procedural listings with a global.

Simple Global

$gvar = "Hello everyone!";

function showOff()

{

echo $GLOBALS['gvar'];

}

showOff();

?>

|

Global With Changes

$gvar = "Hello everyone!";

function showOff()

{

echo $GLOBALS['gvar'];

}

function fixUp()

{

$GLOBALS['gvar']="If it weren't for treats, dogs would rule the world.";

}

fixUp();

showOff();

?>

|

The ouput is wholly different for these two programs when the function showOff() is called:

- Hello everyone!

- If it weren’t for treats, dogs would rule the world.

As programs grow in size and complexity, the problem of globals grows proportionately. (If multiple programmers are involved, the problem grows exponentially!).

Now let’s look at the same issue in a class with a global variable.

class Alpha

{

public $gvar = "Hello everyone!";

public function __construct()

{

echo $GLOBALS['gvar'];

}

}

$worker1 = new Alpha();

|

It throws an error:

Notice: Undefined index: gvar in ….

Rather than trying to find a clever way to get globals into classes, using either the keyword global or the associative array $GLOBALS, let’s just say that a focus on visibility in classes will better serve further discussion of global scope when it comes to OOP encapsulation. (Visibility will be discussed in an upcoming post.)

Local Variables in Classes and Methods

Local variables work with methods in the same way as they do in unstructured functions. The locality of the variable does not matter in terms of return to a call or request. As with all other visibility, that depends on the method. The following example shows a local variable named $local in multiple methods with different content and different visibility. The Client class has a local variable in the constructor function, $runner. The following listing shows a request from within a class and by an external client.

ini_set("display_errors","1");

ERROR_REPORTING( E_ALL | E_STRICT );

class LocalReport

{

public function __construct()

{

echo $this->showOff1() . "

|

The output is:

All good things come to pass.

Fatal assumptions: He will change; she won’t change.

We serve the public (visibility)!

Whether to use local variables or class properties in OOP development depends on the purpose of the application under development. I tend to go for private properties to better insure encapsulation, but local variables can be handy in certain types of implementations. In either case, neither is subject to the problems associated with global variables.

Superglobals

Superglobals in PHP are automatic predefined global variables available in all scopes throughout a script. Most PHP developers are familiar with $_GET and $_POST, but other superglobals such as $_COOKIE, $_SESSION and $_SERVER are commonly used as well. Elsewhere on this blog, injection attacks through superglobals have been discussed, but here I want to look at the relationship between OOP/Design Patterns and superglobals.

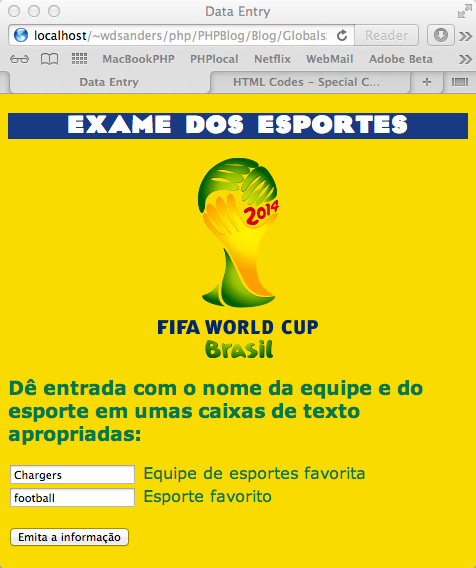

To get a good idea of the “superness” of superglobals, consider a typical OOP program where the requesting class is a client. It calls a class that uses a superglobal. Also, to acknowledge Brazil’s 2014 World Cup hosting, and the publication of Learning PHP Design Patterns in Portuguese (Padrões de Projeto em PHP), I thought I’d create the UI in Portuguese as shown in Figure 1:

Figure 1: Data input module

The HTML data entry is a simple one, asking for the user’s favorite team and favorite sport. They are saved in the super global elements, ‘team’ and ‘sport’ and then sent off using the post method. The following HTML code was used:

DataEntry.html

|

You’ll have to excuse my poor Portuguese. In English it asks to enter your favorite team and sport. (As a long-suffering Chargers fan, you can see the sample entry in Figure 1.) Also, it needs some CSS, lest you think me a total savage:

brazil.css

@charset "UTF-8"; /* CSS Document */ /* 06794e (green), f8d902 (yellow), 1b3c83 (blue), ffffff */ body { font-family:Verdana, Geneva, sans-serif; color:#06794e; background-color: #f8d902; } h2 { font-family: "Kilroy WF", "Arial Black", Geneva, sans-serif; color: #ffffff; background-color: #1b3c83; text-align: center; } img { display: block; margin-left: auto; margin-right: auto; } |

The client class (SuperClient) is little more than a trigger to call a class to process the superglobals. However, the client has no superglobals itself. This is significant in that SuperClient.php is called by the HTML document (DataEntry.html).

SuperClient.php

include_once('SuperGlobal.php');

class SuperClient

{

private $superGlobal;

public function __construct()

{

$this->superGlobal = new SuperGlobal();

}

}

$worker=new SuperClient();

?>

|

So the question is,

Will the super global $_POST be accessible to the SuperGlobal class called by the client?

Let’s see.

SuperGlobal.php

class SuperGlobal

{

private $favoriteTeam;

private $favoriteSport;

public function __construct()

{

$this->favoriteTeam = $_POST['team'];

$this->favoriteSport = $_POST['sport'];

echo "Minha equipe favorita é $this->favoriteTeam.

|

When you run the program, your output will look something like the following:

Minha equipe favorita é Chargers.

Meu esporte favorito é football.

That shows that a superglobal can be accessed from even the most encapsulated environment. In the sense that the HTML Document called the SuperClient and yet the superglobals were available in the SuperGlobal object should tell you (and show you) that once launched from an HTML document a superglobal can be accessed from any PHP file communicating directly or indirectly with the originating HTML document.

Can Superglobals Cause Global Trouble?

For superglobals to be a problem, they need to change unexpectedly within a program.

So the first question, we need to ask is, Can superglobals be changed once they are sent from an HTML document?

We showed that superglobals can get inside an encapsulated object, but can they be changed or do they maintain the values set by the HTML document? The following is a test to find out. With a slight change to the SuperGlobal class and a couple more objects, we can find out.

Step 1: Change the SuperGlobal class to the following:

SuperGlobal.php

//Include new class

include_once('GlobalChanger.php');

class SuperGlobal

{

private $favoriteTeam;

private $favoriteSport;

public function __construct()

{

$this->favoriteTeam = $_POST['team'];

$this->favoriteSport = $_POST['sport'];

echo "Minha equipe favorita é $this->favoriteTeam.

|

Step 2: We need a class to change the values of the superglobals and call another object to display the changes in the same super global.

My friend Sudhir Kumar at PandaWeb.in from Chennai, India is a cricket fan; so I decided to use his favorite team and sport to replace whatever team and sport is entered.

GlobalChanger.php

include_once('SuperChanged.php');

class GlobalChanger

{

public function __construct()

{

$_POST['team']="Team India";

$_POST['sport']= "cricket";

$caller = new SuperChanged();

}

}

?>

|

Step 3: Finally, we need to see if the new team and sport has been changed in the application.

SuperChanged.php

class SuperChanged

{

private $newTeam;

private $newSport;

public function __construct()

{

$this->newTeam=$_POST['team'];

$this->newSport=$_POST['sport'];

echo "

|

Starting with the same html document initially used, we can now see that indeed the superglobal values have been changed, and they are quite available throughout the program.

Minha equipe favorita é Chargers.

Meu esporte favorito é football.

Now my favorite team is Team India.

And my very favorite sport is cricket.

As you can see, the GlobalChanger object changed the original values. Furthermore, it is clear that we were using the same superglobal array in the SuperChanged class when the $_POST values were passed to private variables and displayed using the echo statement.

Obviously, a PHP programmer cannot simply drop superglobals. Further, even though we can change their values, that doesn’t mean we should change them or even have an occasion to do so. But, we need to be aware of the problems with global variables. After all, superglobals are global variables, even in an encapsulated environment.

Conclusion

Two important points need to be emphasized here:

- Don’t use global variables.

- Where you have to use superglobals, don’t change their values dynamically in PHP.

Like everything else in programming there are exceptions, but remember that globals, while having a purpose, often loose that purpose in OOP programs and structured design patterns. When using superglobals, keep in mind that they are true globals and they can be changed, but only if the developer assigns them different values after they’ve been assigned values in HTML. As true globals, they can cause the same kinds of problems that any other globals can. So treat them more like constants, and let their originally assigned values from the HTML form stay put.

Protect Yourself

Protect Yourself

Recent Comments