Putting HTML to Work

Putting HTML to Work

At some point in OOP development with PHP, I quit putting little PHP code snippets in HTML. I either left all PHP out of HTML or encapsulated HTML in a PHP heredoc string inside a class. In that way, all PHP would be part of an OOP order without any loose ends. That may seem overly fussy, but it avoids the slippery slope of degenerating back into sequential programming——patchwork quilt programming.

However, such a practice should not disallow HTML from helping out in an OOP project. A lot of times, I found myself sifting through class and method options using more conditional statements than I wanted in the Client. I realized that I could just pass the class name directly to the Client from a superglobal with origins in an HTML input form. Likewise, I could do the same for methods, and this has become a useful standard operating procedure.

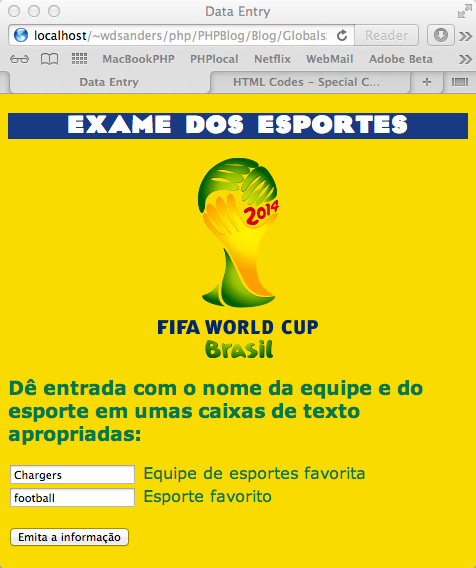

To better illustrate using the HTML UI in launching a selected class object, the following application uses the color and number input elements with both class and method information stored in HTML element values. Both are trivial, but help illustrate the point: (Use Firefox, Chrome or Opera–neither Safari nor Internet Explorer implemented the HTML5 standard color input element.)

![]()

![]()

It’s odd in a way that PHP developers (myself included) are so used to using HTML UIs for data input into MySql databases or making other choices, but few use the UI for calling classes and methods. However, it’s both easy and practical.

Where to Put the OOP in HTML?

You can place class and method names as values anywhere in form inputs that you’d put any data passed to PHP as superglobals. One input form I found useful is the hidden one. It’s out of the way, and you can build forms around the class with other superglobal inputs as methods. Using radio button inputs is another nice option because you can use them either for calling classes or methods with the mutual exclusivity assurance of knowing that not more than one will be called from a given group. To get started, take a look at the HTML:

< !DOCTYPE html>

|

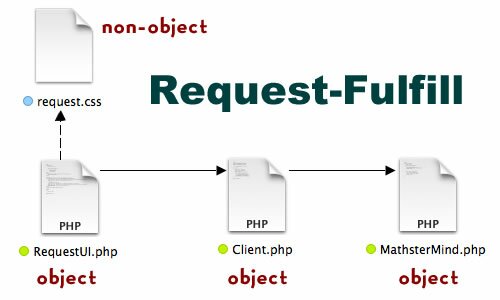

The code has two forms, alpha and beta, and you can think of them as I/O for two different classes. The feedback is returned to the iframe named feedback. Both forms have the action calls to Client.php. So the general plan is:

Client → Class->method()

In the alpha form, the class is ColorClass and the method is doColor()—both in hidden input elements. The name for the class element is “class” and the name for the method element is “method.” All the user does is to choose a color that is passed through the superglobal associated with the color input element.

In the beta form, the class is MathClass placed in a hidden input element. The user chooses either a division or modulo operation from the two radio input elements where the names of the appropriate methods are stored. Once again, the name for the class element is “class” and with mutually exclusive choices the radio button elements for selecting the method, the name is “method.” In this way, whatever superglobal named “class” will fire the correct class and call the correct method with the superglobal named “method.”

The Client

As usual, the Client is the launching pad for the operations. If your application uses different client classes depending on user choices, it’s an easy matter to have unique client names for different forms. In this particular case, the Client class doesn’t care about the form of origin for the request. It just takes the class superglobal and method superglobal names and generates a call to the appropriate class and method.

As an aside, the Client in OOP should not be as rare as some perceive it to be. In one way or another, users (or non-human request mechanisms) employ some way to request that the software do something. The Client, as a participant in a structure, is in virtually every design pattern in one way or another. Even when the Client is not directly or implicitly in a design pattern, The Gang of Four reference it as related to one of the participants in the pattern. So while this example does not use a design pattern, the Client works perfectly well in any OOP program.

< ?php /* * Set up error reporting and * class auto-loading */ error_reporting(E_ALL | E_STRICT); ini_set("display_errors", 1); // Autoload given function name. function includeAll($className) { include_once($className . '.php'); } //Register spl_autoload_register('includeAll'); //Class definition class Client { private static $object, $method; //client request public static function request() { self::doSuper(); $operation = new self::$object(); echo $operation->{self::$method}(); } private static function doSuper() { self::$object = $_POST['class']; self::$method=$_POST['method']; unset($_POST['class']); unset($_POST['method']); } } Client::request(); ?> |

The Client file first takes care of error reporting and automatically calling classes. One experienced developer told me that adding an error-reporting function was unnecessary because it could be automatically turned on in the php.ini file. That’s true, but since I work with many different PHP environments where I have no control over the php.ini file, I’ve found it to be a good practice. You only have to put it in once place, and it takes care of error reporting for the entire program. Besides, I found that one safeguard against easy hacking is to turn off error reporting so that hackers cannot see the names of the classes involved in the application. For this blog, though, I leave the error reporting on because there’s nothing on this blog I want to hide. (Change the init_set from “1” to “0” to turn off all error-reporting.)

No Returns from Constructor Functions

The first incarnation of this application used the same two forms, but the alpha form only had the class name with the results planned to be sent back for output using a return statement. I kept getting errors, and then I learned that constructor functions (those using the __construct() method) have no returns. All they do is to instantiate the class. If you do not use the __construct() method, there’s an invisible automatic constructor function that does that for your as soon as you call new ClassName().

Continue reading ‘PHP Class Origins: An OOP Job for the HTML UI’

An Easy Start

An Easy Start

The Problem with Globals

The Problem with Globals

Recent Comments