Adding a Context

Adding a Context

A few years back, a post on this blog looked at examples of PHP design patterns that had missing parts. In 2006, an IBM sponsored post introduced PHPers to design patterns in “Five common PHP design patterns.” This was an important post because it demonstrated that far from being the exclusive domain of languages like Java, design patterns were applicable to PHP as well. However, of the five patterns, (Factory [Factory Method], Singleton, Chain-of-Command [Chain-of-Responsibility] , Observer, and Strategy) two (Factory and Chain-of-Command) were misnamed and misrepresented, one (Singleton) has since been more-or-less deprecated as a pattern (by no less than Erich Gamma) and the other two were iffy in their implementation.

Like lemmings following each other over a cliff, PHPers often followed each wrong example, further perpetuating the ill-formed pattern. So, when we look at patterns, lest PHP programmers be considered rank amateurs, we need to get patterns right. One of the most common mistakes with the Strategy pattern is either ignoring or leaving out the Context class altogether. In Part I of this two-part series, we saw what a Near-Strategy pattern looks like without a Context class. In Figure 1 of that same post, you can see the class diagrams of the Near-Strategy and Strategy patterns. The example in this post is of a correctly formed Strategy pattern. Play the Strategy example and Download the files with the following two buttons:

![]()

![]()

The Context Participant

To get the Context right, we need to go to the original source, Design Patterns: Elements of Reusable Object-Oriented Software. The Context participant has the following characteristics:

- Configured with a ConcreteStrategy object

- Maintains to reference to a Strategy object

- May define an interface that lets Strategy access its data

At the heart of the Strategy design pattern, the Context and Strategy interact to implement the selected algorithm in the form of a concrete strategy. The key here is,

The Strategy lets the algorithm vary independly from clients that use it.

In order to do this,

A context forwards requests from its clients to its strategy. Clients usually create and pass a ConcreteStrategy object to the context; thereafter, clients interact with the context exclusively.

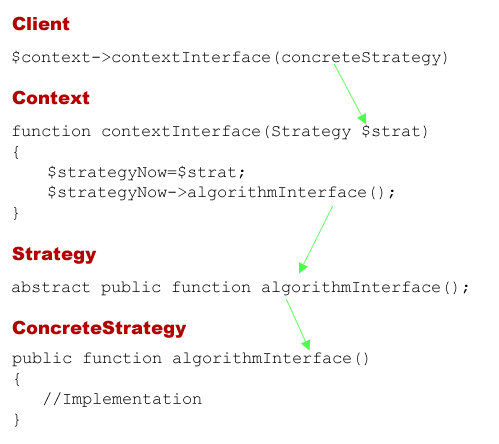

Figure 1 shows the path used in this implementation:

Figure 1: The path through the context to request an algorithm (concrete strategy)

The path begins with the Client creating an instance of a specific concrete strategy (received from the HTML UI) and using that instance as a parameter to make the request through the context. From this point on, the client no longer is in contact with the strategy but instead the context. The context takes the instance passed from the client and makes the request through the strategy interface [algorithmInterface()]. Any client can make similar requests through the context by passing the concrete strategy through its context interface. That can be very handy when your program has more than a single client requiring a strategy.

The Client

In looking at the class diagram for the Strategy pattern, you will not see the a Client class, but the Gang of Four clearly specify the role of the Client. As you can see in the following listing, the Client’s job is pretty simple:

//Automatically load related classes in program

function __autoload($class_name)

{

include $class_name . '.php';

}

Class Client

{

private $useStrategy, $object,$context;

public function __construct()

{

$this->useStrategy=$_POST['strategy'];

$this->object=new $this->useStrategy();

$this->context=new Context();

$this->context->contextInterface($this->object);

}

}

$worker=new Client();

?>

|

I use the Client as a “kick-start” object, including instantiating an instance of itself in the same file it is stored in. This is the only class where such “program-launching” code is necessary. (If you feel queasy about having the Client class launch itself, create a separate trigger file to do it.)

The Context

The Context class is a concrete one, and typically, it’s pretty small. It’s job is to serve as a buffer between any possible number of clients and the concrete strategies (algorithms) they’re requesting.

class Context

{

private $strategyNow;

public function contextInterface(Strategy $strategy)

{

$this->strategyNow=$strategy;

$this->strategyNow->algorithmInterface();

}

}

?>

|

As you can see, there’s not much to the Context class, but it is very important to prevent tight binding between the clients and the strategies they want to use.

The Strategy Interface and Concrete Strategies

For the interface I used an abstract class instead of an interface. I wanted to add a few properties that are used in MySQL operations, including the name of the table used. (You can change the name of the table, but if you do, be sure to create a new one with the module supplied.) The properties are all protected but the strategy method (algorithmInterface()) is public because that method is called by the Context class to access the algorithms in the concrete classes.

abstract class Strategy

{

//Properties all will use

protected $hookup;

protected $sql;

protected $tableMaster="strategy";

//Abstract function

abstract public function algorithmInterface();

}

?>

|

The abstract function is about as generic as they come for this example. You can experiment with different parameters to see which work with the current program. For example, the following two concrete strategies both belong to the “MySQL Family” of operations, but each is quite different:

Inserting Data

class Insert extends Strategy

{

//Field Variables

private $you; // Name of Super Hero

private $town;

private $planet;

private $continent;

private $country;

public function algorithmInterface()

{

$this->hookup=UniversalConnect::doConnect();

//Uses real_escape_string() with text input to make

//injection attacks difficult

$this->you=$this->hookup->real_escape_string($_POST['you']);

$this->town=$this->hookup->real_escape_string($_POST['town']);

//Radio buttons

$this->planet=$_POST['planet'];

$this->continent=$_POST['continent'];

$this->country=$_POST['country'];

$this->sql = "INSERT INTO $this->tableMaster

(you,planet,continent,country,town)

VALUES ('$this->you','$this->planet', '$this->continent', '$this->country', '$this->town')";

try

{

$this->hookup->query($this->sql);

printf("%s have been inserted into %s.",$this->you,$this->tableMaster);

}

catch (Exception $e)

{

echo "There is a problem: " . $e->getMessage();

exit();

}

$this->hookup->close();

}

}

?>

|

As you can see, the Insert class is not much different from the one used in the Near Strategy example in Part I of this series. The algorithms don’t change, but how they are arranged in the larger context does. The primary difference is that all of the concrete Strategy classes rely on the algorithmInterface() method instead of a constructor function. Feel free to add private methods to the concrete algorithms (ConcreteStrategy) to tidy up the operations, but all concrete strategies must be called from the public algorithmInterface() method through the Context.

Adding New Algorithms: The CSV Strategy

I have been working with a biologist doing research on concussions in school sports, and she wanted all of the data in the survey stored in a MySQL table to be converted to a CSV file so that she and her co-investigator could use a spreadsheet for data analysis. Given the flexibility of the Strategy design pattern, this was an easy task:

CSV Strategy

class CSV extends Strategy

{

private $survey=array();

public function algorithmInterface()

{

//Create Query Statement

$this->hookup=UniversalConnect::doConnect();

$this->sql ="SELECT * FROM $this->tableMaster";

try

{

$result = $this->hookup->query($this->sql);

printf("Select returned %d rows.", $result->num_rows);

while ($row = $result->fetch_assoc())

{

array_push($this->survey,$row);

}

$result->close();

}

catch(Exception $e)

{

echo "Here's what went wrong: " . $e->getMessage();

}

$this->hookup->close();

$fp = fopen('place.csv', 'w');

foreach ($this->survey as $fields)

{

fputcsv($fp, $fields);

}

fclose($fp);

echo "CSV file with the name 'place.csv' created successfully.";

}

}

?>

|

Using the same interface (abstract class) as the other family of algorithms in the Strategy pattern, the CSV concrete strategy worked without having to add anything other than a few lines of PHP.

What’s The Difference Between a “Real” Strategy and a “Near” Strategy?

The difference between the NearStrategy non-pattern in Part I and the Strategy pattern in this post is in the Context class. By cutting off direct communication with the Client and ConcreteStrategy classes, the Context class loosens the bindings between any single request from a client and the concrete strategies. In small simple programs like this example, that may not make a big difference, but in larger programs, especially ones where different clients may be using the same set of strategies, there could be binding problems. By sending requests to the Context to be forwarded to the concrete strategies, we avoid such problems. In small programs, the Strategy pattern may look like overkill, but as with all design patterns as the programs increase in both complexity and size, you’ll be glad to have a design that buffers requests by clients through a Context and the algorithms they want to use.

Copyright © 2014 - All Rights Reserved

0 Responses to “PHP Strategy Design Pattern Part II: Add a Context”