Back to Basics

Back to Basics

Whenever I venture outside of PHP, which has become more regular as I’m working on app development in both iOS and Android. The former is Objective C and the latter, Java. Both languages are embedded in OOP and design patterns. It is during these ventures abroad (so to speak) that I’m reminded of some core issues in good OOP. I usually notice them when I realize that I’m not exactly paying attention to them myself.

Don’t Have the Constructor Function Do Any Real Work

When I first came across the admonition not to have the constructor function do any real work, I was reading Miško Hevery’s article on a testability flaw due to having the constructor doing real work. More recently, I was reviewing some materials in the second edition of Head First Java, where the user is encouraged to,

Quick! Get out of main!

For some Java and lots of C programmers “main” is the name for a constructor function, but I like PHP’s __construct() function as the preferred name since it is pretty self-describing. “Main” is a terrible name because the real main is in the program made up of interacting classes.

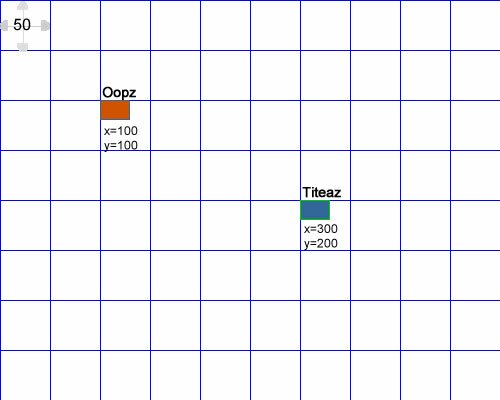

In both cases, the warning about minimizing the work of the constructor function is to focus on true object oriented applications where you need objects talking to one another. Think of this as a series of requests where a group of people are all cooperatively working together, each from a separate (encapsulated) cubicle, to accomplish a task. By having the constructor function do very little, you’re forcing yourself (as a programmer) to use collaborative classes. Play the example and download the code to get started:

![]()

![]()

A General Model for PHP OOP

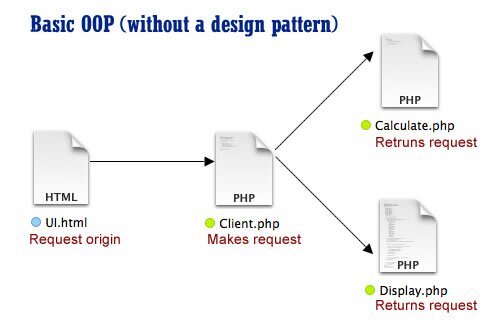

As a nice simple starting place for PHP OOP, I’ve borrowed from the ASP.NET/C# relationship. ASP.NET provides the forms and UI, and C# is the engine. As an OOP jump-off point, we can substitute HTML for ASP.NET and PHP for C#. The Client class is the “requester” class. The UI (HTML) sends a request to the Client, and the Client farms out the request to the appropriate class. Figure 2 shows this simple relationship.

Figure 1: A Simple OOP PHP Model

If you stop and think about it, OOP is simply a way to divide up a request into different specializations.

Avoid Conditional Statements if Possible

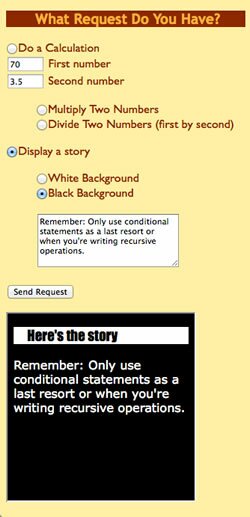

Figure 2: Requests begins with a UI built in HTML

Suppose for a second that all of your conditional statements were taken away. How, using the information sent from the HTML UI to the Client class can the selections be made without conditional statements? (Think about this for a moment.)

Think, pensez, pense, думайте, piense, 생각하십시오, denken Sie, 考えなさい, pensi, 认为, σκεφτείτε, , denk

Like all things that seem complex, the solution is pretty simple. (Aren’t they all once you know the answer.) Both classes were given the value of their class name in their respective radio button input tags. Likewise, the methods were given the value of their method names. With two radio button sets (request and method), only two values would be passed to the Client class. So all the Client had to do was to use the request string as a class name to instantiate an instance of the class, and employ the following built-in function:

call_user_func(array(object, method));

That generates a request like the following:

$myObject->myMethod;

In other words, it acts just like any other request for a class method. By coordinating the Client with the HTML UI, that was possible without using a single conditional statement. In this next section, we’ll now look at the code.

Continue reading ‘PHP OOP: Back to Basics’

Encapsulating Movement

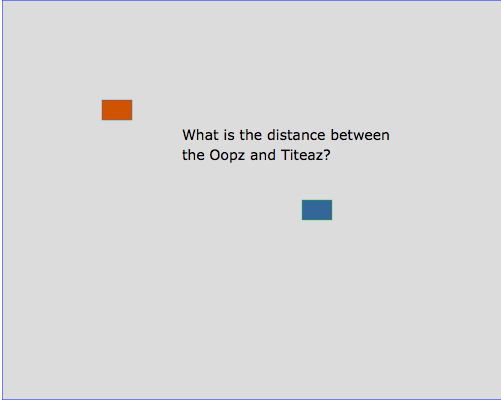

Encapsulating Movement Distance in 2D Space

Distance in 2D Space

Getting the Basic with PHP-MySql

Getting the Basic with PHP-MySql

Obey the State!

Obey the State!

Recent Comments