Adding a Context

Adding a Context

A few years back, a post on this blog looked at examples of PHP design patterns that had missing parts. In 2006, an IBM sponsored post introduced PHPers to design patterns in “Five common PHP design patterns.” This was an important post because it demonstrated that far from being the exclusive domain of languages like Java, design patterns were applicable to PHP as well. However, of the five patterns, (Factory [Factory Method], Singleton, Chain-of-Command [Chain-of-Responsibility] , Observer, and Strategy) two (Factory and Chain-of-Command) were misnamed and misrepresented, one (Singleton) has since been more-or-less deprecated as a pattern (by no less than Erich Gamma) and the other two were iffy in their implementation.

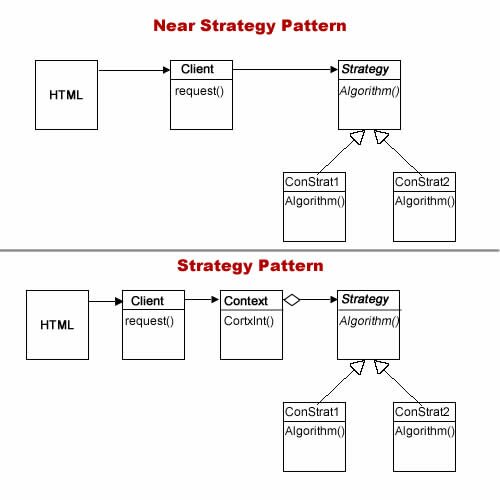

Like lemmings following each other over a cliff, PHPers often followed each wrong example, further perpetuating the ill-formed pattern. So, when we look at patterns, lest PHP programmers be considered rank amateurs, we need to get patterns right. One of the most common mistakes with the Strategy pattern is either ignoring or leaving out the Context class altogether. In Part I of this two-part series, we saw what a Near-Strategy pattern looks like without a Context class. In Figure 1 of that same post, you can see the class diagrams of the Near-Strategy and Strategy patterns. The example in this post is of a correctly formed Strategy pattern. Play the Strategy example and Download the files with the following two buttons:

![]()

![]()

The Context Participant

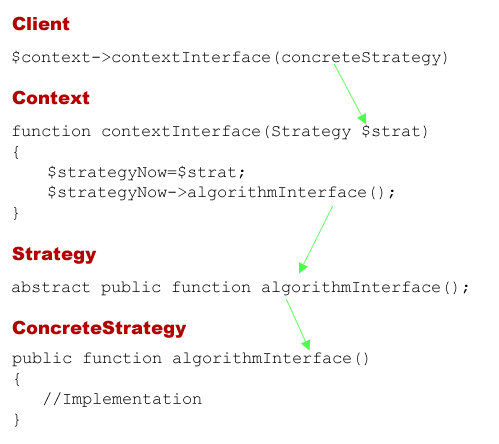

To get the Context right, we need to go to the original source, Design Patterns: Elements of Reusable Object-Oriented Software. The Context participant has the following characteristics:

- Configured with a ConcreteStrategy object

- Maintains to reference to a Strategy object

- May define an interface that lets Strategy access its data

At the heart of the Strategy design pattern, the Context and Strategy interact to implement the selected algorithm in the form of a concrete strategy. The key here is,

The Strategy lets the algorithm vary independly from clients that use it.

In order to do this,

A context forwards requests from its clients to its strategy. Clients usually create and pass a ConcreteStrategy object to the context; thereafter, clients interact with the context exclusively.

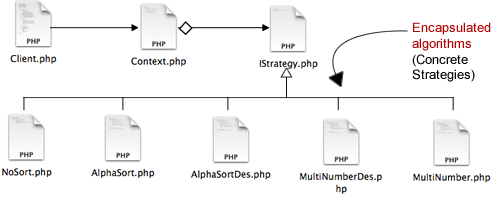

Figure 1 shows the path used in this implementation:

Figure 1: The path through the context to request an algorithm (concrete strategy)

The path begins with the Client creating an instance of a specific concrete strategy (received from the HTML UI) and using that instance as a parameter to make the request through the context. From this point on, the client no longer is in contact with the strategy but instead the context. The context takes the instance passed from the client and makes the request through the strategy interface [algorithmInterface()]. Any client can make similar requests through the context by passing the concrete strategy through its context interface. That can be very handy when your program has more than a single client requiring a strategy.

Continue reading ‘PHP Strategy Design Pattern Part II: Add a Context’

Why ‘Near’ Strategy?

Why ‘Near’ Strategy?

Organizing Algorithms

Organizing Algorithms

Recent Comments